Krång-Johan Eriksson

Krång-Johan Eriksson also known as "Liss-Majt-Johan", "Bullas-Johan" or simply "KJ" was born4th October 1889 Östnor, Mora.

KJ grew up in Tåmåsbyn, Östnor, and early on showed signs of entrepreneurship. As a young man, he would cycle around Mora selling bread and cookies that he had bought from his older sister Anna, who owned the café Bullas Kafé, which was almost across the road from Carl Andersson’s factory. KJ once said, that at age 12, he earned as much from his business as an adult man with a permanent job.

He also learned wood and bark crafts, from the times he would spend his summers in Kansbol with his grandfather Bälterkall and was able to manufacture items to sell.

KJE worked for brief periods in various Östnor factories,

including a period at Frosts Knivfabrik and FM

Mattsson. In the Frosts factory, he put handles on the knives and learned

the basics of the knife-making business. KJ would earn piecemeal, by the number

of handles he had put on blades. As he was mechanically skilled he was asked to

help to repair the single-engine driving every machine in the factory, so he

demanded to be better paid accordingly, he earned very little per hour compared

with being paid by the number of knives assembled. Erik Frost didn’t take the

request well, and after a discussion, was basically thrown out of the factory. Some anecdotes are saying that he was actually expelled from the factory

by Erik Frost leading him by the ear!

KJ served in the military as an Artillerist in Stockholm in

1910. At the age of 21, he had already managed to save so much money that he

could afford to go to a restaurant at least once a week.

After his military service, he tried forestry work, but very

quickly realized that because of his predisposition for rheumatism he was not

suitable for this profession.

After many experiences in different careers, he also

considered, like many others in Mora, to emigrate to the USA but decided to try

the knife-making business first.

Lok-Anders Mattsson

He grew up in a poor environment. His father died very early

and his mother had to take care of him. His economical situation also

influenced his education. His mother couldn’t afford to send Anders to Kråkberg

to complete his studies, so he only took the lower grade classes. Even so, he

had relatively good grades, most ironic is the fact that in science and geometry

he had the lowest grades.

He soon started working as a laborer to contribute to the

family on the important transport route between Falun and Röros in Norway. There

were lots of tiring tasks for laborers such as helping to load and unload, monitoring

the loads and attending to the horses, and much more. The days were long

enduring the cold, rain, and snow.

At age 14, he got his own fora/wagon. During one of the

trips, Anders experienced a terrible event that would mark him for life, one of

his buddies got lost in the forest and was found the next day frozen to death.

This happened in July 1898.

He also worked at the sawmill, however, working at the sawmill, was hardly

something that appealed to Anders with his mechanical-technical

talents.

He seems to have been employed at F.M. Mattsson. He was probably

hired as a toolmaker/designer at F.M.M. after the years at Beus & Mattson.

Like so many others at the

Eriksson & Mattssons Knivfabrik

Above: 1912. Krång-Johan Eriksson (left) and Lok-Anders Mattsson.

KJ was four years younger than Anders and they had both

worked together at F.M. Mattsson as well as Beus & Mattson and there they got

to know each other’s talents and strengths.

KJ was the businessman while Anders was more interested in manufacturing and

the mechanical aspects of the business.

Together they founded Eriksson & Mattssons Knivfabrik in

1912. Eriksson was 23 and Anders 27.

They got a loan to build a workshop on Ander’s land

and buy equipment for the factory.

Until their workshop was finished, they settled at Jöns

Persson's forge (that was located nearby the location of Eriksson &

Matsson factory). Most of the tools and

machines needed, were designed and made by Anders at Jöns

Persson's forge.

In the book GMF - En företagsmonografi av Lennart Thorslund

book a few references about Anders

“He was a real honorable man. He never had any intention to

fool anyone but he got fooled himself by others, I've been told. He wasn't a

very good businessman, he was too honest for that. But by then his mind was elsewhere,

he was always thinking about some other project.” (Karl

Bälter)

“He was a very polite and kind man, very honest” (Einar

Eriksson, KJE’s son)

The first helper of the company was Lissmajt-Erik, KJ's brother,

who was good at forging.

Skeri (Stikå) Jannes Aronsson kept the Book KJ ERIKSSON 1912 - 1992, Skeri

(Stikå) Jannes Aronsson tells:

“Lok-Anders was the one performing the hardening all the

time, and then I would stand next to him and anneal the knives. It was

something that they had started at Frosts. There they had a fire pit where they

could anneal the knives in. At that time, they only forged knives with steel

inlay (laminated steel), and they were very sensitive (brittle) because one

man would harden them and another man would anneal them. KJ made a big pot in

which they melted a mixture of tin and lead in which they dipped down the

knives, and then they were annealed at once.”

KJE heated the blades in the melted lead/tin mixture then rapidly

cooled in oil or saline (quenching) and then re-heated to a much lower temperature in the melted lead/tin (annealing). Ref: News article 1946 Sondagem 13 Oktober 1946

Thomas Eriksson also says regarding the tempering process “When

I was young we still had that kind of furnace with a big pot with melted lead/tin

and after some seconds the blades were red and then quickly dipped in quenching

oil. After being cooled off they had to be annealed separately, otherwise, the

blades would crack spontaneously after a couple of days.”

In the beginning, only No.1 and No.2 size knives were

produced.

With the manufacturing aspect organized, now came the difficult

part, setting up the sales channels and distribution.

At the time, the sales and distribution were completely

controlled by Böhlmark & Co that already had the exclusive rights for

Frosts branded knives. Eriksson & Mattsson, were initially unable to reach

a distribution agreement with Böhlmark & Co, probably because neither Böhlmark

nor Frost wanted newcomers to the scene to threaten their monopoly. Of course,

the episode when KJE got fired from Frost due to insubordination, didn’t help

either.

So they had to equip their own sales force with horses and sleds

to reach the market outside Mora. Sales were good, however, an agreement was

eventually reached with Böhlmark & Co in 1914, for a 5-year contract.

It is not clear how much the two partners agreed to in the

terms of the contract. Probably Anders wanted to get rid of the sales concerns

even if it represented an extra cost, while KJ was more skeptical of a deal.

This will be fundamental a few years later.

The contract included the entire production of the knife

without sheath (Böhlmark & Co would probably buy the sheath directly from Ströms

Knivslidsfabrik) for 5 years from 26 February 1914 to 26 February

1919. The price of a dozen would-be 3.25 SEK for the comparable model of the No.2

that E. Frost makes (it’s quite curious mentioning one of the competitors in

the contract) although the price would be indexed to the price of the steel,

that at the time of the signature of the contract was 0.75 SEK per Kg. The

price would include the delivery.

During the First World War (1914-18) it was very difficult

to get hold of grindstones. They were able to buy some grindstones from the

recently closed-down Långö

in Älvdalen. The stones were wider than the ones they usually used, so they

had to be split into 3 sections with a stone saw. Source: Book KJ ERIKSSON 1912 - 1992

Book KJ ERIKSSON 1912 – 1992 Skeri (Stikå) Jannes Aronsson mentions:

Regarding the grindstones, Bo Eriksson made an interesting remark: “The grindstones were up to 1200 mm diameter. Sometimes the workers speeded up the rpm to get a better grinding result but oftentimes the stone cracked and pieces of the stone flew around and workers got hurt”

With the Böhlmark & Co contract ending, Lok-Anders wanted to renew it but KJ wasn’t that sure. There was a big discussion outside the workshop between both partners. The workers inside the workshop witnessed firsthand the end of Eriksson & Mattssons Knivfabrik.

In the GMF book, it’s also mentioned an episode before the previous discussion mentioned, where Anders dismissed all the workers and closed the workshop while KJE was away for compulsory military service. When KJ returned, Anders justified the action by saying that things were not working and there were no orders. The business resumed operations. Most likely Anders didn’t want to fight but rather preferred to pursue his own ideas and constructions.

Anders's financial skills, as mentioned before, were not the best. At first, he was in charge of the money, to pay the wages, etc. But things changed, no orders would be processed until KJ took care of it.

In 1918, partners of Eriksson & Mattssons Knivfabrik went their separate ways when Lok-Anders sold his share in the company to Krång-Johan for 3200 Swedish kronor. They did not have the same vision and opinions on things, and probably with some backstage Böhlmark & Frost influence, a separation ensued. A loan of 25 years of the land where the first factory building was situated and later KJ’s family home was built, that was owned by Lok-Anders, was included in the 3200kr buyout. The contract also specified that Anders would be released from any obligation from the contract with Böhlmark & Co, so KJ would have full control of the future of the relationship with Böhlmark & Co.

Other interesting details contained in the contract

“I hereby sell my share, half, of the smithy building … and half of all work machines and work tools, which are in the said building, as well as half of a circular saw and a grinding machine, which are outside the said village. The purchase includes: partly a coal house, 1 woodshed, and retirement, all standing on the above-specified land area;”

Skeri (Stikå) Jannes Aronsson in Book KJ ERIKSSON 1912 –

1992, also comments how they would source the wood needed to make charcoal for

the forges:

“KJ and I have been out floating on the river as well. He

bought the wood far up the river. Erik Östberg made a timber-raft and sailed it

down Dynggrav and then we would go there and take that raft, me

and KJ. It was a long raft. I remember how birds ran around on the timber on

the raft. KJ said that we should have had the coffee pot with us too, so we

could have made some coffee up there. We sailed on that raft down to

Segelstaden. This was 1920 when the spring flood was massive. Olpers-Olsson

had a small hut over there by the river, and the charred that wood, and it

turned out very well.”

Like all the other makers from that era, KJE did not have a

sheath production, he bought all their sheaths from Ströms Knivslidsfabrik. In

1919 alone, Ströms Knivslidsfabrik made 46,200 sheaths for KJ

The 1920s were a difficult time for the knife manufacturers

in Mora. KJ's daughter Olga remembers that the storehouse for a long time

"was full of knives".

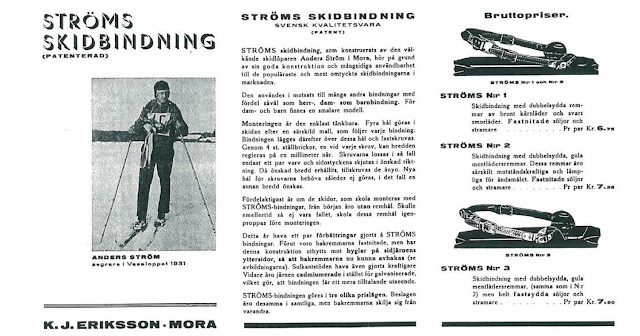

At the end of the 1920s, Anders Ström (from Ströms

Knivslidsfabrik) designed and patented a ski binding called the Ström

binding. KJ Erikssons Knivfabrik bought the patent and started producing

them. It was a very popular product in the 1930s and helped keep production

running during the severe depression until the rat trap binding took over the

market about ten years later. The bindings were protected from rust by black

oxidation. The recipe for this process was obtained from Mäkärn. Einar Eriksson remembers that the process of producing

the black oxide solution smelled "like when you fry pancakes".

The contract signed

with Anders Ström regarding manufacturing and sales of Ström's ski binding.

Staff in 1925. Fr.v. Frost-Nils

Nilsson, Krång-Erik Eriksson, Johan Lillpers (originaly called Krång Johan Eriksson, changed his name to his mother’s family name Lillpers. Was son of Johan Eriksson brother), Krång-Oskar Larsson, Erik Jönsson

jr, Päres-Anders, Skeri-Emil Aronsson, Skeri-Jannes Aronsson. Source: KJ

Eriksson 1912-1992

Above: Invoice from the KJE to F.A. Andersson 1920s. FAA was buying supplies from KJ

KJE with staff outside the workshop in 1932. Many

familiar names here as well, like Erik Jönsson (Bröderna Jönsson) , Carl Ström

(Ströms Knivslidsfabrik) and Skeri-Jannes Aronsson. Source: book KJ Eriksson

1912-1992

On the left 1919 - Skeri-Jannes Aronsson; on the right, Krång-Einar

Eriksson and Skeri-Jannes Aronsson.

A special note about Skeri-Jannes Aronsson or Webb-Jannes.

He was a very important work for KJE and is referred to a few times in this

article, he was one of the people who witnessed the agreement when Lok-Anders

sold his part of the company to KJE, is to him that KJE confided how important

the sports knife was to the company. The faithful servant

"Webb-Jannes" also received when he retired, on top of the state

pension, an extra monthly sum from the company as a thank you for his help in

difficult times. Krång-Johan or "KåJi" as he was called, could never

have imagined that Webb-Jannes would live to be 106 years old. Webb-Jannes left

KJE in the 1970s after working there for 54 years.

Ads from 1938. Source

In the 1930s one other product was introduced to the catalog, scissors

made from laminated steel. They were very popular and were the gateway to

many wholesalers. (the production was completely phased out in 1968) Today they

are still a very appreciated collector’s item.

Picture Source: book KJ Eriksson 1912-1992

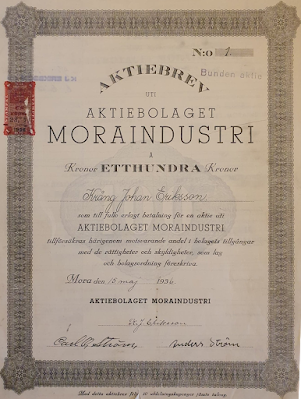

In 1935, KJE started AB Moraindustri, a sanitary fittings factory, together with brothers Carl and Anders Ström from Ströms Knivslidsfabrik.

Just a few years later, in 1939, the Ström brothers sold their share to KJ Erikssons Knivfabrik and started their own fittings factory under the name Bröderna Ström.

Advertising of KJ Eriksson and AB Moraindustri intended for

the Mora exhibition 1948. Source: book KJ Eriksson 1912-1992

Huge quantities of knives were made for clients such as

Bergans in Norway.

In 1937 Einar Eriksson, son of Krång-Johan Eriksson became

CEO of the company. In 1939, Einar had to serve in the military defending the

Swedish borders and Krång-Johan Eriksson stepped in again as CEO role

temporarily until 1945.

In April 1943, FM

Mattsson’s forge burned to the ground on the night of the 15th. With

the help of KJ Eriksson, that lent their facility in the evenings and the

weekends, they were able to do some production although limited. This is a good

example of Östnorsanda” or “Östnor spirit” where the companies have helped each

other when in need.

For a few years in the 1940s, wood gas fan housings were produced.

The equipment was mounted on cars during WWII when no gasoline for cars was

available. With a small stove, you burned wood slowly, creating a burnable gas

that could run the engine.

The scout line continues to develop and grow. The scout line

and the side business AB Moraindustri were fundamental to the survival of the

company and overcoming the recession in war times. It is said, that KJ confided

to one of his employees Webb-Jannes Aronsson: “Without the scout knives, you

and I would be seeing some tough times right now.”.

Some examples of scout knives produced by KJE from different

eras

Staff in 1946. Standing from left: Karl Böhlin, Kans-Erik

Eriksson, Nils Legranäs, Rudolf Andersson Ivar Thomsson, Nils Pettersson, Otto

Sköld, Ingvar Matsson, Axel Lassis, Karl Thorildsson, Janne Hansjons, KE

Matsson, Gunnar Modin, Manne Persson, Einar Andersson, Erik Fjäll, Tysk-Viktor

Eriksson, Uno Eliasson, Rune Bengtzelius, Stikå-Bror Andersson, Elof Jansson,

Ivan Persson, Viktor Stenis, Nils Hållams and Bälter-Sven Andersson. By the

wall are Evert Andersson and Viktor Pers. Sitting from left: Per Stenkist ,

Fritz Andersson, Oddvar Nordby, Ida Larsson-Liljedal, Henning Grannas, Hins-Karin,

Sven Vallin, Hugo Olsén, Edvin Liljedal, Krång-Anders Eriksson

(Lissmajt-Anders), Verner Liljedal and Olle Hed. Source: book KJ Eriksson

1912-1992

A curious history: The premises had been constructed without

permission from the authorities, but KJ was able to show a paragraph saying

that the construction of buildings requiring no more than three construction

workers could take place without special permission.

The new premises also included the manufacture of leather

sheaths. Unica sheaths were now purchased from a company from Hållsta (They

used some tools that came from Frost, which had a sheath production since WW2. (It is the sheath

production that moved to Norway, Haugrud, that makes that sheath today)

Above, kitchen knives were included in the range in the 1950s. Source: book KJ Eriksson 1912-1992. Below is some new, old stock still in

the basement of MORAKNIV today

KJE introduces the scout knives with plastic handles in the

late 1950s. The bright plastic handles were still made separately and had to

be assembled manually, just like a wood handle. Plastic was a novel

contemporary material and plastic handle knives still enjoyed higher status

than those with a wood handle. A new workshop was built for the company’s first

injection mold department.

In a Morakniv blog post, https://morakniv.se/en/morakniv-stories-en/when-knife-making-was-part-of-the-home, Thomas Eriksson mentioned during 1940 and 1950 its was usual for the company to

distribute the so-called "homework". A company driver would go around town to distribute assignments to family house wolds. This task would be like stitching sheaths, etc. Its family would be paid by job performed like the number of sheaths.

Thomas remembers his mother, sewing N.54 sheaths with aluminum wire and dying the white cotton ribbons in colors like red, yellow, and green so they could later be sewn in the sheath of the No. 49, 50, 51, and 52. The edges of the aluminum strip used were very sharp and would cut the fingers in the process of tightening process.

In the final 1950s or earlier 1960, the shares of AB-Carl Andersson starts to change hands. The widow of Erik Andersson (youngest son of Bud-Carls) and his son, sold their shares to Arthur Andersson, that then sold at least some of them to Jannes Hallin from Hallin & CO.

In 1961, one of the other siblings did not want the family

business in the hand of Jannes Hallin, so he turned to Einar Eriksson (son of

Krång-Johan Eriksson and CEO of KJE at the time) and asked him if KJ would be

interested in buying his shares. A public auction was held for the totality of

the company and KJE won, Hallin just could not match KJ's bid.

After the auction, there was an immediate takeover/entry and

Einar immediately made sure that the locks were changed. Einar also felt that

the workshop should probably be guarded at night for the first time and Nils

Legranäs, who married KJ ́s daughter Lilly, had to take the first night’s watch.

At three o'clock in the morning, a car was driven up. It was Jannes

Hallin came and tried to enter, however, he failed because the

locks were already changed. Einar apparently had a feeling of what to expect

after the takeover. AB-Carl Andersson was fully integrated in KJ Eriksson.

From AB-Carl Andersson, came the Ice drills product line that was the foundation of the current Mora ice drill production until it was sold on to Rapala in Finland during 2013-14.

The 1960s was at this time, KJ Erikssons Knivfabrik acquired its first polishing machine, made by Åkerblom in Eskilstuna. Machine polishing made it possible to phase out manual side trimming, saving time

and making knives cheaper. However, the art of side trimming continued for some

models for several years and was completely abandoned eventually in The 1970s.

Sven Rombin, KJE worker, 1960s. This particular grinding

stone is currently on display at the factory as a kind of museum piece and the

wall behind is now grated and built-in with newer parts of today's Mora

knife. Ref

In early 1960, after KJ’s grandson, Bo Eriksson spotted

a KJE knife in Capri, Krång-Johan Eriksson commented “they (his knives) seems

to find their way into every corner of the world”

In 1961 FMMattsson the company had no choice but to shut down the knife

production and everything related to knives was put up for sale.

There were many companies involved in the process. Frost

reached the conclusion that all the machinery was old so didn't show any

interest. KJ Eriksson had interests in the business but was not allowed to

participate. Both companies, FMM and KJE (AB MoraIndustri was one of the families)

were competitors, in the water faucets business and this was the main reason

why FMM refused to sell the knife production to KJE.

AB Moraknivar ends

up making the deal. In November 1961, FMM sent out an information letter

to its knife customers that it had handed over its knife production to AB

Morakniv in Färnäs and therefore cannot receive any more customer orders.

However before they finalized the business, AB Moraknivar declared

bankruptcy. So, Ingmar Norlin from FM went without further notice by truck

with a team of workers to Färnäs and brought back what had been delivered

already. Ingmar then bought the knife production privately (as a front) and

then sold it directly on to his shooting buddies, Einar and thus KJ Eriksson in

1962.

The main objective of this deal was probably to exclude any other person that wanted to start up competing businesses from entering the

market.

Because of the age of the machinery, few if any, ended up on

the KJ Eriksson production floor. The few models that were integrated into the

KJE catalog was the No.650,

later re-named No.

1700. Check the full article on this model here

New facilities were built for KJ Eriksson’s Knivfabrik and

AB Moraindustri on Bjäkenbacken in Östnor in 1967. Their intensive ice drill

production was expanding at an impressive rate.

KJ Eriksson Knivfabrik’s founder Krång-Johan

Eriksson died shortly after his 75th birthday in 1964.

Bo Eriksson (son Einar Eriksson and grandson of Krång-Johan Eriksson) becomes CEO of the company in 1968.

Around 1967-68, AB Carl Andersson's staff and machines also moved to Bjäkenbacken in Östnor.

The 1970s see the born of several star products:

in 1975 the 1701 Mora "Jägaren" was

introduced and was the product of the decade. With its grip-friendly handle and

brutal design, the Mora Hunter was the obvious macho alternative. The fact that

it was an excellent hunting knife was an added bonus. See the dedicated article

about this knife here

In 1976, KJ Erikssons Knivfabrik introduced model

510 with a plastic handle which was an instant success. For 2

years, Luna company (Swedish hardware distributor) received exclusive rights for

511/546, after this period Luna had a special version with the Luna logo on the

sheath. Less than 30 years later, outdoorsmen in the USA dubbed the knife “The

Wilderness Blade” in the US magazine Field & Stream. Ever since, it is

considered to be the ultimate survival knife due to its simplicity, its

reasonable price, its superior sharpness, its reliability, and its unsurpassed

durability, in all categories. Mora of Sweden, Morakniv has a faithful

following of enthusiasts on social media who pleaded with Morakniv to bring

back production of the 510 which they duly did.

After a negative media debate started by a Swedish hand

surgeon because the classic model didn't have a finger guard (see below), KJE in

conjunction with his largest customer, Luna, launched the 511 Luna safety

knife. It was an instant success, breaking record sales that are still unbeaten

after 30years.

"Morakniv Syndrome" as it is known by hand

surgeons refer to the troublesome nerve and flexion injuries that occur when,

for example, during a fishing trip, you have to cut with a knife in a boat

with slippery fingers and your hand slides down over the edge of the handle and

you cut your fingers severely.

In a study from 1975-78, of all injured men, mostly during

leisure activities and then most often during a fishing trip. Young men in

their 20s were clearly overrepresented.

From the magazine article Råd & Rön 1979, nr 10. "Between 70 and 100 people come to Swedish hospitals every year because they have cut the finger-tendons of one hand with an ordinary mora knife. All are boys, most 5-25 years old. Healthcare costs per year injured can be estimated at at least half a million kronor."

Age distribution in 34 patients with flexion injuries in the

fingers caused by a slice with a knife without bars. Average age 20 years.

Ice drill production continues to grow. In 1974, the factory

added about 2,500 sq meters for knife and ice drill production. In total, the factory is

In 1974 the production is 6000 to 8000 knives and 600 ice drills per day.

Around 1974 KJE stopped using laminated steel.

The two companies KJ Erikssons Knivfabrik and AB Moraindustri merged in 1980 to form one company, KJ Eriksson AB.

Mattsons Jarnhandel hardware store was owned by KJE and FMM. Before the store, the build housed Mattsson Mekaniska. It is still possible to read on the second floor of the building "And. Mattsons Mek. Verkstads A-B"

Meanwhile, Frosts Knivfabrik in the mid/late 1980s almost fell into the hands of its Finnish competitor, Fiskars. A group of shareholders wanted FM Mattsson to step in and save the knife company’s position in the village. FMM together with KJE (FMM and KJE owned together, the local hardware store) stepped in and purchased 72% of the capital of Frost, 36% each.

Fiskars also tried to buy KJ Eriksson but was refused. Ref: 2002-11-11 MT sid 04 (K J Eriksson avvisade Fiskars)

Question marks are straightened out: Two companies entered

as co-owners in Frosts

The question marks around the future of Frost's knife

factory has now been settled. At least in terms of ownership. It became clear

on Tuesday that the two Östnors companies FM Mattsson and KJ Eriksson each buy

35% of the shares in Frosts Knivfabrik AB. The remaining 30% is owned by a

group of previous owners.

It is intended that Frost's knife factory will continue to

be operated as a single unit.

According to representatives of the two knife factories

Frosts and KJ Eriksson, the deal was actually initiated by the Finnish giant

Fiskars OY AB, which made overtures to buy both KJ Eriksson and Frost. There

was thus a great risk that the old classic Mora knife would not only end up in

foreign hands but would also be manufactured abroad. According to the owners,

the agreement that has now been reached will ensure that Morakniven's future is

secured, precisely in Mora.

DIFFERENT ASSIGNMENTS

The old management at Frost's knife factory had extensive

negotiations with Fiskars from Finland regarding a sale. That was during last

year. However, these negotiations and the purpose of them met with a patrol of

other partners and since then relations have been a bit cool between the

ownership groups at the knife factory and in recent times, various rumors have

circulated. The old company’s management with Per-Erik Frost as CEO has

immediately left their positions at the knife factory and the acting CEO is now

Anders Brask.

In addition to the contacts with Frost's knife factory,

Fiskars has thus "fished" with KJ Eriksson and placed a bid for that

company. But the result of this carousel was that FM Mattsson and KJ Eriksson

buy 70 percent of Frost's knife factory stock.

COMPETITORS

Bo Eriksson, who is production manager at KJ Eriksson, says

that Frosts and KJ will continue to work as independent units and thus remain

competitors. On the other hand, it is not excluded that there will be an

exchange of production technical features and other collaboration functions.

The goal is to jointly cut even larger market shares. Frost's knife factory is

the largest in the country for knives. KJ Eriksson also has ice drills on his

program, as well as a subcontracting unit.

As for FM Mattsson, the water fittings giant, the company

that once also had knife production on its program. CEO Olle Mattsson says that

he sees it as a great advantage that FM Mattsson can broaden its manufacturing

area and he believes that Morakniv is a profitable product.

600 EMPLOYEES

FM Mattsson, Frost's knife factory, and KJ Eriksson are all

three old well-known companies in Östnor. FMM has around 400 employees. Frosts

have 80 and KJ has 115 employees. This means that a total of about 600 employees

FMM and KJ have previously had good experiences of cooperation through co-owner

Mattson's iron in Mora and therefore it was now decided to go into that deal to

save the Mora knife to remain in town.

Representatives of the employees at Frost's knife factory

believe that the now announced deal has partially restored calm in the

workplace. There is perhaps still a slight skepticism about the business, that

it should lead to forms of rationalization that reduce employment. It is also

hoped from the employee representatives at Frost's knife factory will have knowledgeable company management, without specifying further wishes.

5 million knives go out from Mora every year. Half of the

production is exported. There will be Mora knives from Mora also in the future

...

STEN WIDELl”

Above: In 1987 the

board decides on the largest single machine investment ever. Company Heusler AG

in Switzerland was commissioned to produce a machine for rolling spiral screws

for ice drills. Source: book KJ Eriksson 1912-1992

Krång-Johan Eriksson did not live to see the full circle when the knife factory in which he learned to make knives became his subsidiary in 1988. At that time, Frosts Knivfabrik had about 90 employees.

The end of the 1980s bring another commercial hit, the

711 (red = Carbon) and the 746 (blue stainless).

Image from 1990 catalog

In 1990 a new automated plant is inaugurated. Hand-operated grinding machines were replaced by fully automatic plants where blades are stored in cassettes that are transported between the different processing operations. Knife blades were automatically picked and placed into the injection mold for handle molding, finished knives were removed and inserted into the sheaths, and then finally, untouched by human hands, packaged in display cartons. Shift work was introduced and overseeing and maintenance of the robotic plants replaced much of the manual labor and craftsmanship

Automated knife production made by Battenfeldt in Austria. Source:

book KJ Eriksson 1912-1992

Pictures from KJE factory Source: book KJ Eriksson 1912-1992

In 1991 KJE releases a new best-seller, the Mora 2000 and it was once again an instant success. Read the complete article about this model here

KJ workforce. In the year 2000, there were 94 employees

In 2003 Bo Eriksson steps down as CEO and the dilemma of

succession and the complexities in the traditional family-own company give

places to a new external board of directors, being appointed for the company

and for the first time, a non-family member was recruited to the position of

CEO, Carin Nises.

In January 2004, KJ Eriksson AB sold the water and

sanitation division (ex- AB Moraindustri) to FM Mattsson Metal, in order

to concentrate on knives and ice drills.

The really big change started when KJ Eriksson AB acquired

the remaining shares in Frosts Knivfabrik in three stages. The first step was

taken in 1988, second in 2002, through the acquisition of FM Mattsson’s 36% of

shares, and the third in 2005 when the Brask brothers sold the rest of their 28%

shareholdings. Frosts Knivfabrik became a subsidiary of KJ Eriksson AB.

In 2005 KJE is renamed Mora of Sweden AB

In 2006, Frosts Knivfabrik operations are transferred to the

parent company.

Mora of Sweden AB is born.

Photos: some of the new old stock present today on the

basement of MORAKNIV

Notes: some of the headcounts are based on the pictures of

that year. The number 2006 already reflects the merge of Frost in KJE.

Locations

Patents

Specials thanks

To Thomas and Bo Eriksson, grandsons of Krång-Johan Eriksson

for all the info shared with me and time spend review all the info.

Thanks to Gunnel Mattsson-Frost, grandchild of Lok-Anders

Mattsson

And to Gary Jones for his hours of proofreading

Sources

Book Morakniv - Sedan 1891 ISBN-10 : 9163391082

Book KJ ERIKSSON 1912 – 1992

GMF - En företagsmonografi av Lennart Thorslund

”Hela världen skär med moraknivar” , Mora Tidning 21/12/1938

https://morakniv.se/en/this-is-morakniv/our-history/

http://www.morahembygd.se/wp-content/stigsson/pe0826a22.html

https://grebenschikova.livejournal.com/1410289.html

https://www.solar.se/solarmagasin/sm2/made-in-mora/

https://digitaltmuseum.se/search/?q=K.%20J.%20Eriksson%20kniv&o=0&n=80

https://www.jof.se/aktuellt/knivskarpt-fran-mora/

https://www.bergans.com/en/about-us/our-history

http://kniver.blogspot.com/2009/10/11.html

Мора, это история лучших ножей!!!

ReplyDeleteKJ is the backbone of what we know today as Morakniv. They are the last manufacturer of knives in Mora after E.Jonsson factory burned down early this year.

Delete